Whitley Awards for ACE White Stork projects

Since 1994 the Whitley Awards have been awarded annually. They are one of the largest nature conservation awards available, recognizing outstanding efforts by leading local conservationists whose work is based on sound science and which fully involves local communities.

Dr. Karen Aghababyan’s research on the white stork is focused in the Ararat Valley, home to agriculture for thousands of years. During the Soviet years the wetland areas were reduced by Government draining and although they are slowly recovering a new threat has emerged – Armenia has been granted $200 million for infrastructure development, including draining the Ararat wetlands at the base of Mount Ararat, for conversion to agriculture. For centuries the White Stork has been regarded with great affection in Europe. Although they were once prolific, the intensification of agriculture and draining of wetlands has resulted in a decline in the populations. Traditionally storks like to keep their feet wet feeding in wetlands ditches or ponds where they catch frogs, lizards and small rodents. Although many Armenians feel indifferently towards wetlands, White Storks are seen as a cultural icon. They are seldom persecuted and when storks nest close to people, on anything from telegraph poles to roofs, it is a sign of good luck. Dr. Aghababyan has made birds popular in Armenia, teaching bird identification courses in English, Russian and Armenian. Using the White Stork as a flagship species, Dr. Aghababyan launched ‘Nest Neighbors’; working with farmers and villagers, to increase public understanding of storks and their habitat. By becoming involved in wetland conservation, Armenians are starting to take notice of what is being decided for natural resource use at local, national and international levels. Now, over 500 families are involved in ‘Nest Neighbors’ and regularly monitor the stork population.

HRH The Princess Royal and Sir David Attenborough (not pictured) presented the Whitley Award to Dr. Karen Aghababyan in 2007 at London’s Royal Geographical Society. It was the first time anyone from Armenia has won the Award.

“Nest Neighbor” Celebrations

During the fall, Acopian Center researchers conduct award ceremonies to honor “Nest Neighbors”. At these celebrations, certificates and gifts are awarded, accompanied by songs and plays about storks performed by school children and speeches delivered by village representatives.

Dr. Aghababyan launched ‘Nest Neighbors’; working with farmers and villagers, to increase public understanding of storks and their habitat. By becoming involved in wetland conservation, Armenians are starting to take notice of what is being decided for natural resource use at local, national and international levels. Now, over 500 families are involved in ‘Nest Neighbors’ and regularly monitor the stork population.

Tree and Shrub List for Armenia

Partial List of Trees and Shrubs for Armenia

After the massive tree-cutting period of the early 1990s, caused by the economic blockade and the energy crisis, there was much discussion about deforestation in Armenia. During that period people were cutting trees everywhere and removing anything wooden to burn for heat!

Tree planting is the best action to take in order to mitigate deforestation and tree removal. However care must be taken not to unwittingly harm the environment. One may ask how is it possible to harm the environment by planting trees?

There are many non-Armenian tree species (non-native species), which are invasive and can aggressively occupy an area by crowding out and eventually replacing native, indigenous species of trees. Unfortunately, in Armenia, after the massive tree-cutting period of the early 1990s the planting of invasive species became a common practice, mostly due to lack of awareness of the ecological detriment that planting of invasive species can cause.

Below is a partial list of trees and shrubs which are growing in Armenia. We generally recommend planting only species that are labeled as ‘native’. Any species labeled ‘invasive’ should never be planted and actually should be removed whenever possible. These invasive species have a particular ability to produce thousands and thousands of seeds that can germinate, grow and eventually shade out native species.

There are other ecological reasons for planting only native species of plants having to do with the interactions of insects and wildlife with the plant species.

Scientific Name | Common Name | Native Habitat | Native? | Notes |

Acer negundo | boxelder | USA, southern Canada | non-native | invasive |

Acer platanoides | Norway maple | Europe | | |

Acer pseudoplatanus | Planetree maple, Sycamore maple | Europe, western Asia (cultivated for centuries) | | |

Acer tataricum | Tatarian maple | southeast Europe, western Asia | | |

Acer trautvetteri | Caucasian maple | Caucasia, northern Turkey | native | |

Aesculus hippocastanum | Horsechestnut | Greece, Albania | non-native | |

Ailanthus altissima | tree of Heaven | China | non-native | extremely invasive |

Albizia julibrissin | mimosa, silk tree | Iran to central China | non-native | |

Amygdalus communis | almond | Middle East | | |

(Prunus dulcis) | | | | |

Armeniaca vulgaris | apricot | Armenia | native | |

(Prunus armeniaca) | | | | |

Betula pendula | | | | |

| | | | | |

Betula litwinowii | | | native | |

Biota orientalis | Oriental arborvitae | Korea, Manchuria, northern China | non-native | |

(Thuja orientalis) | | | | |

Buddleia davidi | butterfly-bush | China, Japan | non-native | |

Buxus sempervirens | boxwood | southern Europe, northern Africa, western Asia | | |

Caragana arborescens | Siberian peashrub | Siberia, Mongolia | | |

Carpinus caucasica | Caucasian hornbeam | Europe, Caucasus | native | |

Catalpa bignonioides | catalpa | southern USA | non-native | |

Cercis siliquastrum | Judas tree | southern Europe, western Asia | non-native | |

Cornus sanguinea | European dogwood | Europe, western Asia | native | |

Cotoneaster horizontalis | rock cotoneaster | western China | non-native | |

Cydonia oblonga | quince | Caucasus | native | |

Elaeagnus angustifolia | Russian-olive | southern Europe, central Asia,

Altai , Himalayas | native | |

Fagus orientalis | oriental beech | northwest Turkey, Caucasus, Iran | native | |

Forsythia suspensa | weeping forsythia | China | non-native | |

Fraxinus excelsior | European ash | Europe, southwestern Asia | native | |

Fraxinus pennsylvanica | green ash | USA, Canada | non-native | |

Gleditsia triachanthos | honeylocust | USA | non-native | |

Hippophae rhamnoides | seabuckthorn | Europe to China | native | |

Hibiscus syriacus | rose-of-sharon | India, China | non-native | |

Jasminum fruticans | wild jasmine | Mediterranean, Asia Minor | native | |

Junglans regia | English walnut | southeastern Europe to China | native | |

Juniperus virginiana | eastern redcedar | east and central North America | non-native | |

Koelreuteria paniculata | goldenrain tree | China, Korea, Japan | non-native | |

Ligustrum vulgare | European privet | Europe, northern Africa, southwestern Asia | native | |

Lonicera maackii | Amur honeysuckle | Manchuria, Korea | non-native | invasive |

Maclura pomifera | osage orange | USA | non-native | |

Malus domestica | apple | western Asia | naturalized | naturalized nearly everywhere in the world |

| | | | | |

Malus orientalis | | | native | |

Melia azedarach | Chinaberry | India to China | non-native | |

Morus alba | white mulberry | China | naturalized | |

Paulownia tomentosa | empress tree | China | non-native | |

Picea orientalis | Oriental spruce | Caucasus, Asia Minor | | |

Pinus brutia | Turkish pine | west of Caspian Sea to Greece | | |

Pinus eldarica | Afghan pine | ?Caucasus, Russia, Afghanistan, Pakistan | | |

| | | | | |

(Pinus brutia) | | | | |

Pinus halepensis | Aleppo pine, Jerusalem pine | Europe | non-native | |

Pinus nigra | European black pine, Austrian pine | Europe, Balkans, Crimea | non-native | |

P. n. subsp.pallasiana | European black pine | Europe to Turkey | non-native | |

Pinus pinea | stone pine | Europe, Mediterranean | non-native | |

Pinus ponderosa | ponderosa pine | western North America | non-native | |

Pistacia mutica | pistachio | Caucasus | native | |

(P.atlantica var. mutica) | | | | |

Pistacia vera | common pistachio | western Asia | non-native | |

Platanus orientalis | Oriental planetree | southeastern Europe, western Asia | native | |

Populus alba | white poplar | southern Europe to central Asia | native | |

Prunus armeniaca | apricot | Asia | considered native | |

Prunus avium | sweet cherry | Europe, western Asia | native | |

Prunus cerasifera | cherry plum, myrobalan plum | Europe, Caucasus, western Asia | non-native | |

(Prunus mirobalan) | | | | |

Prunus cerasus | sour cherry | Europe, southwest Asia | non-native | |

Prunus domestica | common plum | Europe, southwest Asia | non-native | |

Prunus mahaleb | rock cherry | central Europe to central Asia | native | |

Prunus persica | peach | China | non-native | |

Prunus tomentosa | Nanking Cherry | China to Japan | non-native | |

Punica granatum | pomegranate | Caucasus | native | |

Pyrus communis | European pear | Europe, western Asia | non-native | |

Pyrus caucasica | Caucasian pear | Europe, western Asia | native | |

( P. communis subsp. caucasica) | | | | |

Pyrus demetrii | pear | Caucasus | native (globally threatened endemic species) | |

Pyrus salicifolia | willowleaf pear | southeastern Europe, western Asia | native | |

Quercus castaneifolia | chestnut-leaved oak | Caucasus, Iran | | |

Quercus macranthera | Caucasian oak | Caucasus, western Asia | | |

Quercus pontica | Armenian oak | Caucasus, northeastern Turkey | | |

Quercus robur | english oak | Europe, Caucasus, Asia minor | non-native | |

Ribes aureum | buffalo currant | North America | non-native | |

Ribes nigrum | black currant | northern Europe, northern Asia | non-native | |

Robinia pseudoacacia | black locust | USA | non-native | |

| | | | | |

Rosa sp. | | | native | |

Salix babylonica | Babylon weeping willow | Asia | non-native | |

Sambucus nigra | elderberry | Europe, northwest Africa, southwest Asia, western North America | native | |

Sophora Japonica | pagoda tree | China, Korea | non-native | |

Sorbus aucuparia | mountain ash | Europe, western Asia | native | |

Spiraea x vanhouttei | | | non-native | |

Symphoricarpos albus | Snowberry | USA, Canada | non-native | |

Tamarix araratica | Salt-cedar | | native | |

Taxus baccata | English yew | Europe, northern Africa, western Asia | native | |

Thuja occidentalis | American arborvitae | eastern USA, eastern Canada | non-native | |

Ulmus laevis | European white elm | Europe to Asia | native | |

Weigelia florida | old fashioned weigela | Japan | non-native | |

Ziziphus jujube | Chinese date | southeastern Europe to Asia | native | |

Invasive Species in Armenia

Invasive species in native and non-native ranges

2007-2008

Armenia, ECRC/AUA

USA, University of Montana, University of California

Argentina, Universidad Nacional de La Pamba

Turkey, Adnan Menderes University

Georgia, Institute of Botany

Romania, Institute Of Biological Research

Hungary, Insttute of Ecology and Botany

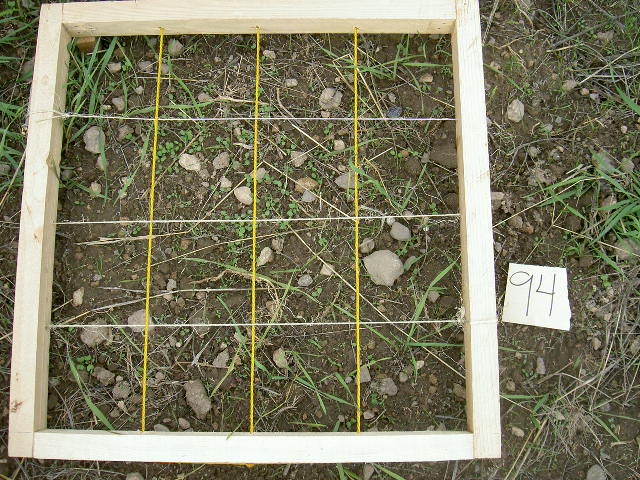

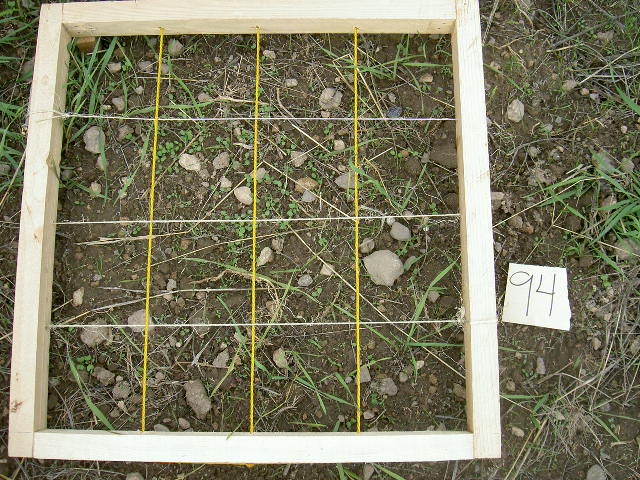

Studying germination in the native and non-native range of a species can provide unique insights into processes of range expansion and adaptation; however, traits related to germination have rarely been compared between native and nonnative populations. In a series of common garden experiments, we explored whether differences in the seasonality of precipitation, specifically, summer drought vs summer rain, and the amount and variation of annual and seasonal precipitation affect the germination responses of populations of an annual ruderal plant, Centaurea solstitialis, from its native range and from two non-native regions with different climates. We found that seeds from all native populations, irrespective of the precipitation seasonality of the region in which they occurred, and non-native populations from regions with dry summers displayed similarly high germination proportions and rates. In contrast, genotypes from the non-native region with predominantly summer rain exhibited much lower germination fractions and rates and ecology. Organisms transported by humans to regions where they are not native (exotics) commonly face novel selective forces, which given enough genetic variation, may trigger novel evolutionary responses. The worldwide distribution of this species encompasses environments with contrasting precipitation regimes within both native and non-native ranges. Specifically, some of the regions where C. solstitialis grows are characterized by a Mediterranean-type climate with wet winters and dry summers, whereas other regions have a precipitation regime in which most of the precipitation falls during the summer, and winters are substantially drier. In all regions, the species germinates primarily in autumn (Sheley and Larson 1994, Hierro et al. 2006, L. Khetsuriani, L. Janoian and K. Andonian unpubl.); thus, winter conditions may affect its survival. Here, by conducting a series of common garden experiments in a growth chamber, we investigated whether contrasting differences in the seasonality of precipitation and changes in surrogates for environmental quality (e.g. precipitation totals) and risk (e.g. inter-annual variation in precipitation) affect germination responses of C. solstitialis populations occurring across its native range and in two climatically distinct non-native regions.

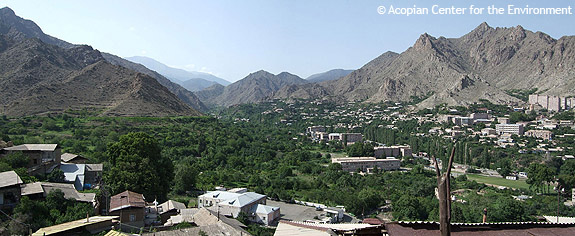

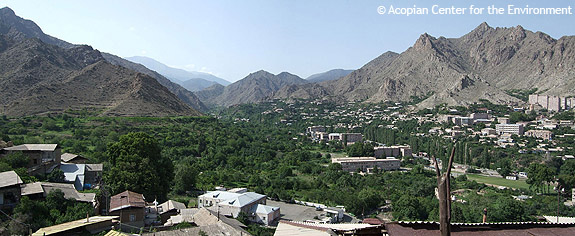

General view of the experimental field in Armenia

To investigate the potential effects of seasonality of precipitation on C. solstitialis germination, we conducted three successive seed collections from populations occurring in regions exepte France, Crete and Armenia, where seeds were pooled within populations. Mean cumulative germination percentages (91 SE) of pappus and non-pappus seeds of C. solstitialis populations plotted against the coefficient of variation of winter precipitation and the probability of occurring a good winter.

Pappus seeds maintained a strong association with variation in winter precipitation (r__0.91, pB0.001), but this relationship did not hold for nonpappus seeds (r__0.36, p_0.172). In addition, germination of both pappus and non-pappus seeds were no longer correlated with the probability of good winters (r_0.44, p_0.117 and r_0.11, p_0.387, respectively). Without Argentina, the association between germination proportions of pappus seeds and variation in annual precipitation improved slightly (r__0.70, p_0.017), whereas the correlation of these proportions with the probability of good years remained non-significant (r_0.39, p_0.150). Finally, as before, germination fractions of non-pappus seeds were not correlated with any of the measures of annual risk, and germination percentages of both seed morphs were not associated with any of the measures describing environmental quality (p_0.250 in all cases).

Clines in these studies corresponded to variation in general climatic patterns, such as changes in climate between northern and southern latitudes (Maron et al. 2004, 2007) or between coastal versus inland environments . In contrast to these results, our comparisons based on general climatic patterns (i.e. summer drought vs summer rain) did not detect parallel clines in germination traits for populations from native and non-native ranges, as all native populations, irrespective of the climate in which they occurred, and non-native populations from the region with a summer-drought climate displayed similarly high germination proportions and rates; whereas non-native genotypes from the region with a summer rain regime exhibited much lower germination fractions and rates. On the other hand, our comparisons based on precipitation variables, which are commonly used as surrogates for environmental quality and risk, showed that for the most abundant seed morph, seeds with a pappus, germination responses of populations in both native and non-native ranges correlated strongly with ‘risk’ experienced during the winter. Specifically, and as predicted by bethedging theory, germination fractions of pappus seeds were lower in native and non-native populations experiencing greater inter-annual variation in winter precipitation (Fig. 4). For non-pappus seeds, however, this correlation was greatly influenced by non-native genotypes from central Argentina, which are from the region with the highest variation in winter precipitation of all the studied regions and exhibited the lowest proportions of germinating seeds in all our experiments (Fig. 2_4); after removing central Argentina from analyses, there was no association between germination fractions of non-pappus seeds and winter precipitation variation. Similarly, germination fractions of both pappus and non-pappus seeds correlated with probability of occurrence of good winters only in the presence of Argentinean variables. Overall, these findings suggest that rather than general climatic patterns, the degree of risk experienced at early developmental stages could exert an important control over the germination strategy of C. solstitialis populations in both native and non-native ranges. In addition, they reveal the largely unique nature among studied populations of seed germination in nonnative genotypes from central Argentina. Germination fractions of pappus seeds were also correlated with variation in annual precipitation, suggesting that overall annual risk could also play a role in the germination behavior of C. solstitialis populations. Indeed, populations experiencing comparable variation in winter precipitation in the native and non-native range tended to display similar germination fractions for this seed type . In contrast, for non-pappus seeds the link between degree of dormancy and level of winter risk does not hold when outlier Argentinean variables are removed from analyses, providing weaker support for bet-hedging across C. solstitialis populations.

Clines in these studies corresponded to variation in general climatic patterns, such as changes in climate between northern and southern latitudes (Maron et al. 2004, 2007) or between coastal versus inland environments . In contrast to these results, our comparisons based on general climatic patterns (i.e. summer drought vs summer rain) did not detect parallel clines in germination traits for populations from native and non-native ranges, as all native populations, irrespective of the climate in which they occurred, and non-native populations from the region with a summer-drought climate displayed similarly high germination proportions and rates; whereas non-native genotypes from the region with a summer rain regime exhibited much lower germination fractions and rates. On the other hand, our comparisons based on precipitation variables, which are commonly used as surrogates for environmental quality and risk, showed that for the most abundant seed morph, seeds with a pappus, germination responses of populations in both native and non-native ranges correlated strongly with ‘risk’ experienced during the winter. Specifically, and as predicted by bethedging theory, germination fractions of pappus seeds were lower in native and non-native populations experiencing greater inter-annual variation in winter precipitation (Fig. 4). For non-pappus seeds, however, this correlation was greatly influenced by non-native genotypes from central Argentina, which are from the region with the highest variation in winter precipitation of all the studied regions and exhibited the lowest proportions of germinating seeds in all our experiments (Fig. 2_4); after removing central Argentina from analyses, there was no association between germination fractions of non-pappus seeds and winter precipitation variation. Similarly, germination fractions of both pappus and non-pappus seeds correlated with probability of occurrence of good winters only in the presence of Argentinean variables. Overall, these findings suggest that rather than general climatic patterns, the degree of risk experienced at early developmental stages could exert an important control over the germination strategy of C. solstitialis populations in both native and non-native ranges. In addition, they reveal the largely unique nature among studied populations of seed germination in nonnative genotypes from central Argentina. Germination fractions of pappus seeds were also correlated with variation in annual precipitation, suggesting that overall annual risk could also play a role in the germination behavior of C. solstitialis populations. Indeed, populations experiencing comparable variation in winter precipitation in the native and non-native range tended to display similar germination fractions for this seed type . In contrast, for non-pappus seeds the link between degree of dormancy and level of winter risk does not hold when outlier Argentinean variables are removed from analyses, providing weaker support for bet-hedging across C. solstitialis populations.

Several mechanisms could be responsible for the genetic differentiation in germination traits of Californian versus Argentinean populations, including coincidental introductions, genetic drift, and natural selection operating on phenotypes formed by either a novel combination of genes or pre-adapted genotypes (i.e. the sorting-out hypothesis _ Mu¨ller-Scha¨rer and Steinger 2004; see Leger and ice 2007 for a comprehensive discussion on these mechanisms). Outcrossing plants partition most of their genetic diversity within, rather than among, populations, which increases the probability of possessing high genetic variation upon introduction because even a few immigrants can carry much of the species’ genetic variation.

Several mechanisms could be responsible for the genetic differentiation in germination traits of Californian versus Argentinean populations, including coincidental introductions, genetic drift, and natural selection operating on phenotypes formed by either a novel combination of genes or pre-adapted genotypes (i.e. the sorting-out hypothesis _ Mu¨ller-Scha¨rer and Steinger 2004; see Leger and ice 2007 for a comprehensive discussion on these mechanisms). Outcrossing plants partition most of their genetic diversity within, rather than among, populations, which increases the probability of possessing high genetic variation upon introduction because even a few immigrants can carry much of the species’ genetic variation.

Full article available in Oikos 118: 529_538, 2009

doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17283.x,

# 2009 The Authors. Journal compilation # 2009 Oikos

Subject Editor: Pia Mutikainen. Accepted 31 October 2008

“Germination responses of an invasive species in native and non-native ranges”

Jose´ L. Hierro, O¨zkan Eren, Liana Khetsuriani, Alecu Diaconu, Katalin To¨ro¨ k, Daniel Montesinos,

Krikor Andonian, David Kikodze, Levan Janoian, Diego Villarreal, Marı´a E. Estanga-Mollica and Ragan M. Callaway

Endemic Wheats of Armenia Project 2008

Armenia, although a small country, is very rich in wild relatives of cultivars, including the ancestors and donors of such important cult ivated plants as bread cereals. The study of wild species of wheat, barley, goat grass, rye and others of the cereal crops represents a large practical interest. Progenitors of cultivars are often carriers of valuable attributes and features, such as, high drought and frost resistance, the ability to grow on relatively poor soils, and resistance to pests and disease. That is why wild relatives are valuable material for the selection of new varieties of cultivated plants.

Armenia, although a small country, is very rich in wild relatives of cultivars, including the ancestors and donors of such important cult ivated plants as bread cereals. The study of wild species of wheat, barley, goat grass, rye and others of the cereal crops represents a large practical interest. Progenitors of cultivars are often carriers of valuable attributes and features, such as, high drought and frost resistance, the ability to grow on relatively poor soils, and resistance to pests and disease. That is why wild relatives are valuable material for the selection of new varieties of cultivated plants.

In addition to this, purely in practical terms, the study of wild relatives of cereal crops are of particular help in understanding the path by which many thousands of years ago the creation of the modern cultivated grasses from wild cereal crops took place, and in giving a more precise definition to the regions where the agricultural civilization arose. From that viewpoint the study of the history of domestic bread cereals helps to shed light not only on the history of agriculture but on the history of humans in a broad sense.

Conserving the rich gene pool of wild relatives of wheat cultivars in Armenia is an urgent concern, as more and more land is disturbed by growing economic activity, land privatization, and other factors. Therefore, it is extremely important to evaluate the different Armenian populations of wheat and other cereals, and to conserve this valuable material. This can be achieved through periodic population monitoring, conservation in situ, and through collection of a seed material for preservation ex situ.

Conserving the rich gene pool of wild relatives of wheat cultivars in Armenia is an urgent concern, as more and more land is disturbed by growing economic activity, land privatization, and other factors. Therefore, it is extremely important to evaluate the different Armenian populations of wheat and other cereals, and to conserve this valuable material. This can be achieved through periodic population monitoring, conservation in situ, and through collection of a seed material for preservation ex situ.

Previously, botanists have conducted numerous comprehensive studies of cereal crops, and also led archeobotanical excavations which shed light on the relatively early stages of the domestication of grasses. This current project will facilitate more comprehensive studies of the populations of wild cereal crops through the use of modern cytogenetic and molecular biology methods.

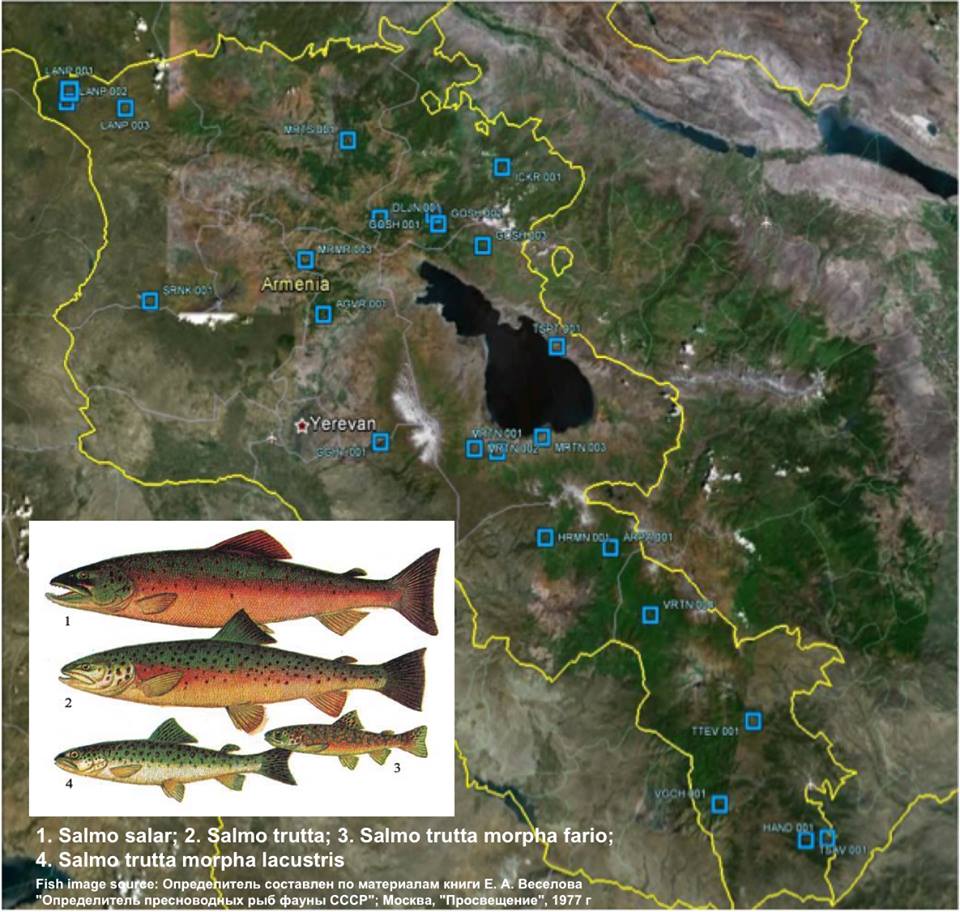

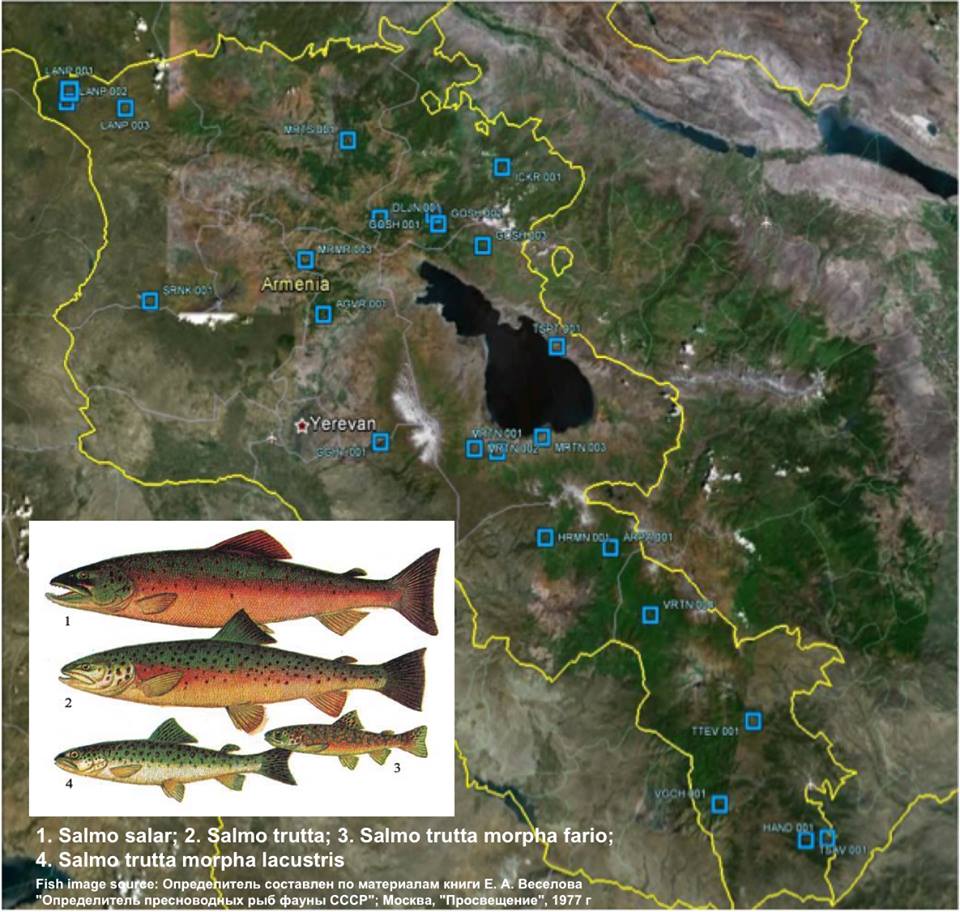

Brown Trout (GIZ)

Reintroduction of the Brown Trout in Armenia’s Rivers Studied by AUA Acopian Center for the Environment

Overfishing in the 1990s has led to a collapse of Brown Trout (Salmo trutta morpha fario) stocks throughout Armenia. This species, once available abundantly in all of Armenia’s provinces, is currently found in fewer than 20% of surveyed rivers. To determine the suitability for its reintroduction, the AUA Acopian Center for the Environment with support from GIZ, the German Organization for International Cooperation, has conducted an extensive survey of physical and chemical properties of 22 rivers and streams in 7 provinces of Armenia.

Overfishing in the 1990s has led to a collapse of Brown Trout (Salmo trutta morpha fario) stocks throughout Armenia. This species, once available abundantly in all of Armenia’s provinces, is currently found in fewer than 20% of surveyed rivers. To determine the suitability for its reintroduction, the AUA Acopian Center for the Environment with support from GIZ, the German Organization for International Cooperation, has conducted an extensive survey of physical and chemical properties of 22 rivers and streams in 7 provinces of Armenia.

“The results of the survey are promising,” says Dr. Karen Aghababyan, chief scientist of the AUA Acopian Center and the study’s principal investigator. “Most rivers studied are suitable for reintroduction of the species. Their oxygen and pH levels were within the range preferred by the Brown Trout, and most sites had appropriate levels of ammonia and carbon dioxide, as well as enough benthic invertebrates to serve as food for the reintroduced fish,” explains Dr. Aghababyan.

In addition to scouting river sites, the AUA Acopian Center researchers found an appropriate brood stock with which to populate the rivers in question. To this end, the Center has collaborated with a fish farm that had Brown Trout captured wild in the Arpa River in 2009. This trout, which has not interbred with other fish species and has not gone through artificial selection, caries all the genes of the wild population and is suitable for introduction into the native stocks.

For many decades, the Brown Trout has been a staple fish in diets worldwide. In most parts of the world, Brown Trout is interbred with local populations, resulting in fish that is genetically different from their ancestors. Very few places on Earth are home to genetically pure Brown Trout. Armenia is one of these places, its mountainous rivers providing protection from interbreeding with non-indigenous species.

A successful reintroduction of a fish species needs more than adequate water conditions and pure breed. “We also need to ensure that the site is protected from poachers. Communities close to these fish populations have to have economic incentive to protect them. Local stewardship of the fish stock has to be worked into the reintroduction,” says Dr. Aghababyan.

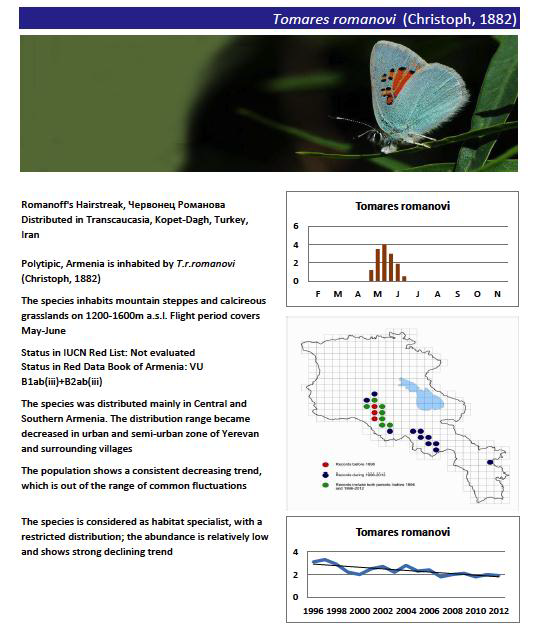

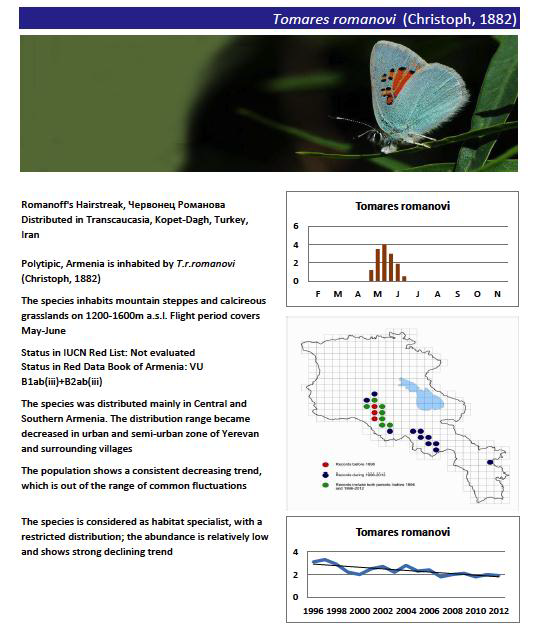

Acopian Field Guide To Butterflies of Armenia

Butterflies are a significant and essential component of global biomes. They comprise about 1% of all described species on the planet and provide essential ecosystem services such as pollination and serve as prey for animal predators. In addition, they provide aesthetic value and are a valuable component of ecotourism. Currently there is no special publication or field atlas regarding the butterflies of Armenia. After having successfully published A Field Guide to Birds of Armenia, the Acopian Center at AUA has started a project to produce a similar guide for Armenia’s butterflies.

Acopian Field Guide to Butterflies of Armenia will have field identification data for every one of the 220 species recorded in Armenia up to date. The guide will also describe 15 new species and many host plants. Much of this information will be published for the first time. The guide will be the result of our long-term investigation of Armenian butterflies and, at the same time, constitutes a first step for the preparation of the Handbook of the Butterflies of Armenia. Both books will be very valuable sources for scientists, tourists and students as well as for environmental education and public awareness.

Butterfly Atlas

This project is intended to fill gaps in the National Strategy of Biodiversity Monitoring regarding the inventory and information management about Armenia’s butterflies and their habitats. At the same time it will strengthen the newly formed partnership with Butterfly Conservation Europe. The project will follow changes in species’ distribution and abundance in butterfly populations, and will examine the damages to their habitat caused by climate change and human interference. Currently, about 60% of the database is complete. In 2013 a complete database and species accounts will be prepared with all related graphics. The publication is expected by August 2014. The first ever Monitoring Atlas on Butterflies of Armenia will be regularly updated thereafter.

Butterfly Monitoring Atlas, sample page.

Winter Feeding of Water Birds on Yerevan Lake

- Acopian Center for the Environment – American University of Armenia

- Yerevan City Municipality

Winter is the most unfavorable period for birds, especially for water birds. Low temperatures, difficult access to food, and short duration of daylight hours serve as the basic negative factors in this period for the vital activity of birds. In addition to natural difficulties, ducks in Armenia also bear anthropogenic influences – among them the construction of on-shore reservoirs, hunting, and poaching out of the hunting season.

A large number of wild ducks gather on Yerevan Lake. According to the winter water bird counting done by specialists on Lake Sevan and Ararat valley, comparatively fewer wild ducks are left in these places, because they are constantly troubled by fishing boats on Lake Sevan and they are harassed and shot by hunters and poachers in Ararat valley. Fortunately, on Yerevan Lake these types of disturbance are absent. Nevertheless, ducks still have to fly from Yerevan Lake to the water reservoirs of Ararat valley in search of food and there they often fall by hunters’ bullets.

Starting from 2002, we have conducted annual winter feeding for water birds in order to keep the ducks on Yerevan Lake.

We use special dry mixtures composed of mixed fodder of barley and oats as well as crumbled dry bread and bread products. We put the bird feeding manger approximately in the middle of the lake and feed the birds once per week. We take sacks of forage on a boat to the floating manger. In addition we survey the bird species composition and count the number of birds on the lake.

We are particularly pleased that school children join us to help us with our feeding procedure. The children, during the feeding activity, also work with trained ornithologists to learn to identify and to appreciate birds in their natural setting.

A special pleasant surprise came in 2008 when we received an initiation for a joint-duck-feeding project on Yerevan Lake with Yerevan City Hall. This has been the first case when we did not seek help from the administrative structures but the administration itself suggested working together. The City Hall provided financial support for obtaining the forage and transporting it to Yerevan Lake. Their support demonstrates that communities can work together in the difficult task of nature protection.

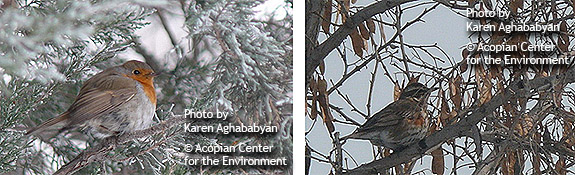

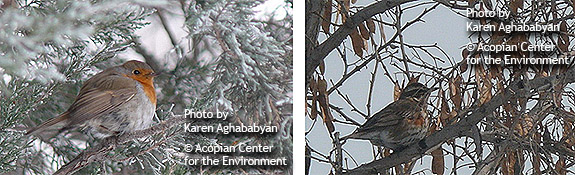

Winter Bird Count 2005 – present (conducted annually)

- Acopian Center for the Environment (ACE)

Acopian Center for the Environment (AUA) in cooperation with volunteers and enthusiasts from different fields, organized winter bird count in Yerevan Botanical garden.

Botanical garden is one of the largest green territories in Yerevan city with half-wild oases. There are several notable species of birds breeding there, such as Levant Sparrowhawk, Hobby, Long-eared Owl, Syrian Woodpecker, Golden Oriole, Common Nightingale, Greenfinch etc. Food availability compels winter bird species to come down and stay in the garden during the winter.

The main goals of the winter bird count are:

- to monitor bird species composition and abundance

- to train volunteers and students in field data collection

- to show our participants how interesting the birdwatching can be.

This count gives us an opportunity to record strictly wintering bird species such us Redwing, Fieldfare, Common Goldcrest, European Siskin, etc.

Participation in winter bird count is a good experience for beginners: “Bird Identification Training”’ (ACE) students, student-zoologists and enthusiasts, who are interested in birds. This gives them an opportunity to study linear bird count technique and to improve bird identification skills. Every year about 8-12 young people join our winter bird counts.

List of recorded bird species in Yerevan Botanical Garden

(2005 – 2009)

1. Eurasian Sparrowhawk

2. Northern Goshawk

3. Common Buzzard

4. Common Kestrel

5. Common Woodpigeon

6. Rock Dove

7. Syrian Woodpecker

8. Middle Spotted Woodpecker

9. European Green Woodpecker

10. Dunnock

11. European Robin

12. Redwing

13. Mistle Thrush

14. Fieldfare

15. Common Blackbird

16. Common Goldcrest

17. Blue Tit

18. Great Tit | 19. Eurasian Jay

20. Common Magpie

21. Western Jackdaw

22. Rook

23. Hooded Crow

24. Common Raven

25. House Sparrow

26. Eurasian Tree Sparrow

27. Common Chaffinch

28. European Greenfinch

29. European Goldfinch

30. European Siskin

31. Brambling

32. Common Linnet

33. Hawfinch

34. Yellowhammer

35. Rock Bunting |

Donation – White Stork Guardian

| |

|

Help support a White Stork nest for a year, and protect one of Armenia’s good-luck symbols. In 2008, more than 600 pairs of storks nested in Armenia. Your $500 donation supports one nest for one year. You will receive a letter confirming your tax deductible contribution from the American University of Armenia. Continue>> |

White Stork Project

The White Stork Project focuses on using the very common and abundant White Stork as a potential bio-indicator of environmental changes in Armenia. By studying migration patterns and reproductive ecology of White Storks, it will be possible to determine potential impacts of climate change and increased pesticide/herbicide use in Armenia. The project is unique in that it uses villagers as citizen scientists or ‘Nest Neighbors’ in the data collection process. Their involvement with the research gives them a better understanding of wildlife ecology and improves the relationship between people and nesting storks. Prior to migration, Acopian Center scientists distribute calendar-questionnaires in the villages and show the villagers how to record information on stork arrival, departure and number of fledglings. After the storks have migrated, Acopian Center scientists collect the calendars and enter the information into a GIS database.

Help support this important project in Armenia by adopting your own stork nest. and becoming a White Stork Guardian.

During the spring, our staff also bands the nestlings and takes water and soil samples in stork feeding areas for later analysis. The Acopian Center for the Environment launched a survey on pesticide use in the Ararat Valley after the first results from soil and water sampling indicated the presence of pesticide contamination. Substantial information on almost 1000 confirmed nest sites in Armenia has been collected through 2009.

Saving the Armenian Gull

The Armenian Gull breeds in Lakes Sevan and Arpi in Armenia. At Lake Sevan it breeds on “Gull Islands” which, as a result of the constant lowering of the water level in the lake, joined the coast, becoming a peninsula, by the end of 1990s. This opened the breeding area to predators and domestic cattle. Predators such as foxes and stray dogs caused much harm to the Gulls by eating their eggs and nestlings. As for domestic animals, they trampled the eggs as they wandered around the island.

The Armenian Gull breeds in Lakes Sevan and Arpi in Armenia. At Lake Sevan it breeds on “Gull Islands” which, as a result of the constant lowering of the water level in the lake, joined the coast, becoming a peninsula, by the end of 1990s. This opened the breeding area to predators and domestic cattle. Predators such as foxes and stray dogs caused much harm to the Gulls by eating their eggs and nestlings. As for domestic animals, they trampled the eggs as they wandered around the island.

The island became open to tourists who frightened the birds and raised panic among them. The human disturbances had the most fatal consequences: eggs were getting too cold during the first period of nesting and in the period of mass hatching the frightened birds were leaving their nests. The parents, in their futile search for their nestlings, were pecking the other lost nestlings to death.

Armenian Gull

The only way to rescue the Armenian Gull was to turn its nesting grounds into an island again. For that purpose, it was necessary to remove the isthmus, digging a channel between the island and the coast. Unfortunately, the corresponding government departments didn’t take an active part, though they were well aware of the urgent need of isolation of the nesting place.

Making of the channel

Thus, on 14 May, 1999, the project workers, equipping themselves with the proper equipment, dug an 18 meter wide breach that was 0.8 to 2.3 meters deep, forming a strait between the land and Gull Island.

In the same year the Center organized a pilot monitoring program of the nesting place of the Armenian Gull on “Gull Island” which testified that our efforts were not in vain. The eggs and nestlings were saved! As a result, an entire generation of Armenian Gulls was conserved.

Each year before the beginning of the nesting season we visit the island and measure the depth and width of the strait in order to determine if we need to step in again.

The Channel

Vultures of Armenia

Why is it important to study vultures in the Caucasus?

The Caucasus Mountains of Armenia are a biogeographic bridge between Europe and Asia. The area is home to a range of raptors (hawks, eagles, and falcons, etc.) including four species of Old World Vultures, Cinereous Vulture (Aegypius monachus), Griffon Vulture (Gyps fulvus), Bearded Vulture (Gypaetus barbatus), and Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus). Determining and tracking the conservation status of Armenian vulture populations is important because they are excellent “biological indicators” of the health of Armenia’s natural and human-dominated landscapes.

What kinds of work and research are we doing?

We conduct surveys of three vulture species in Armenia, and we analyze, publish, and make available to government and conservation groups data on the distribution, abundance, breeding biology, and conservation status of these species.

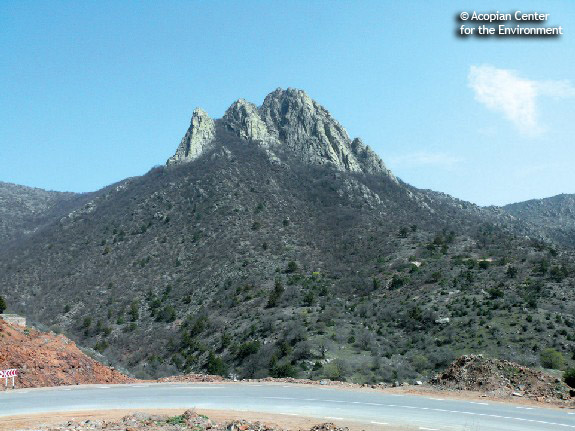

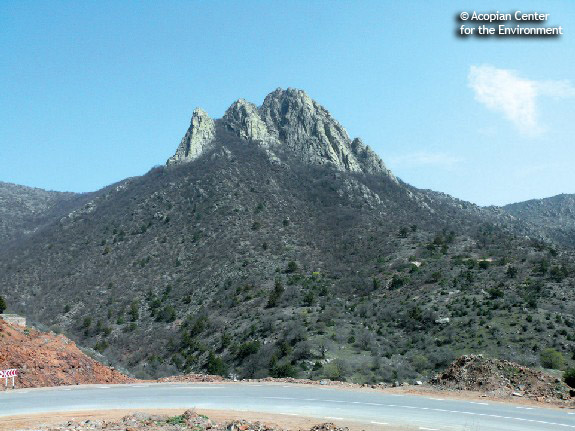

Griffon Habitat Southern Armenia. Click on photo above to enlarge.

What is the goals of our vulture research?

Our overall goal is to determine the conservation status of Armenian vulture populations. We are detailing the distribution, abundance, and reproductive success of Armenian vultures. It helps to identify important areas for raptor conservation in Armenia and establish long-term monitoring schemes for vultures and endangered raptors in Armenia.

Results

Bearded Vulture

There are 8-10 pairs of Bearded Vulture in Armenia. The population of Bearded Vultures in Armenia is stable.

Griffon Vulture

There are 35-40 pairs of Griffon Vultures in 7-9 colonies. Northern population of the species is stable, while the population of Southern Armenia has a tendency to increase.

Egyptian Vulture

There are 40-60 pairs of Egyptian Vultures in Armenia. The population of this species in Armenia stays stable.

Threats

The most serious threat for all the species is a human disturbance, principally from shooting and trapping of adults and the capture of the nestlings, so that the birds can be sold, either as taxidermy specimens or as live birds. Second serious threat is a lack of food (especially in central parts of Armenia), since number of whild ungulates has declined while the changes in the livestock husbandry reduced number of carcasses of livestock in the field.

The results of our work were used for the new edition of the Red Data Book of Armenia and would be useful for the future environmental assessment procedures.

Monitoring of Raptors in the Forest of Aragats Mountain – 2005-2009

- Acopian Center for the Environment

- Yerevan State University

In 2005 we have started a pilot survey of raptors at the forest area of Aragats Mountain, with following objectives:

- to determine a sample area for long term monitoring of forest raptors

- to create a platform for training students in field data collection.

We started the project with full involvement of two students Maro Kochinyan and Hayk Harutyunyan and with occasional involvement of several younger students – volunteers of the “Birds of Armenia” project.

Forest area of Aragats mountain

The forest area of Aragats is rather small (about 2 sq km) but includes almost all diurnal forest raptor species found in Armenia.

Nestlings of Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo)

Particularly we found the following species:

- Honey Buzzard Pernis apivorus – 1 pair

- Black Kite Milvus migrans – 1 pair

- Short-toed Eagle Circaetus gallicus – 1 pair

- Common Buzzard Buteo buteo – 4 pairs

- Lesser Spotted Eagle Aquila pomarina – 1 pair

- Booted Eagle Hieraaetus pennatus – 1 pair

- Sparrowhawk Accipiter nisus – 2 pair

- Goshawk Accipiter gentilis – 1 pair

We continue annual use of this place to train the students and to track Raptors life.

The results of the survey were published in Russian Conservation News No.39 Summer 2005

The effect of pesticides on the populations of Peregrine Falcon in Meghri District of Southern Armenia (2008)

- Acopian Center for the Environment

- Participants: ACE staff and volunteers

- Meghri forestry administration

Acopian Center for the Environment (AUA) with the support of Peregrine Fund and Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in 2008 has conducted a survey of Peregrine Falco in Meghri district.

Red field – study area

Red field – study area

Objectives:

To check the current condition of population (number of breeding pairs) and reproductive success (number of fledglings) to analyze the trend and its possible causes to inspire local community about importance of Raptors through their involvement in the monitoring of the Peregrine Falcon.

Peregrine Falcon оn the nesting cliff

Peregrine Falcon nesting cliffs in the semidesert and forest areas

Peregrine Falcon nesting cliffs in the semidesert and forest areas

Results:

From all the six known Peregrine nests in Meghri region (in 1998-2004) only one successful pair with two fledglings was found, one site was occupied with two adults, but there were no young, and another site with only one adult bird. All other sites were unoccupied.

Analyzing these data and comparing it with previous ones the decline of Peregrine population in Meghri region becomes obvious. We assume that the main reason for the decline is the poisoning, such as sedimentary reservoirs of the copper, molybdenum and gold mines; use of pesticides for agriculture; forest management in frames of pest control.

During the whole project we worked with the local people from Meghri forestry administration and local enthusiasts. This co-operation helped us to do the data collection more effectively and to explain some details about poisoning and poaching.

Researchers of Meghri fores

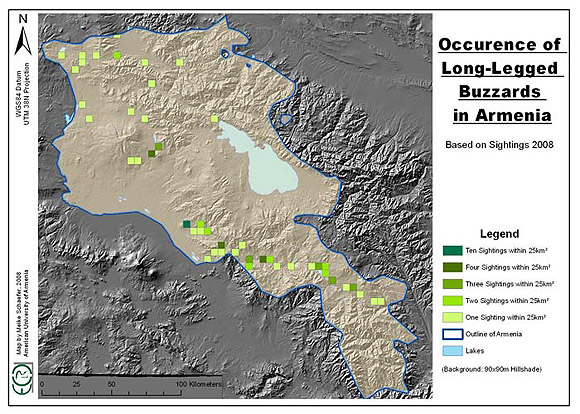

Monitoring of Long-Legged Buzzard Populations in Armenia

- Acopian Center for the Environment

- Yerevan State University

- State Pedagogical University

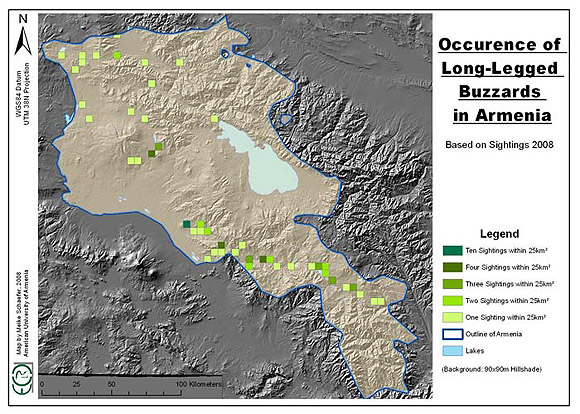

Birds of prey are excellent environmental indicators and flagship species for natural-resource conservation. Increasing of Armenian agriculture and other blanches of industry can have a negative impact to environment. To track the possible influence of industry to our nature we would like to start monitoring of subpopulations of model species in some regions of Armenia.

As a species to be monitored we have chosen Long-legged Buzzard (Buteo rufinus) because it is most common rodent-eating bird that breeds in whole Armenia.

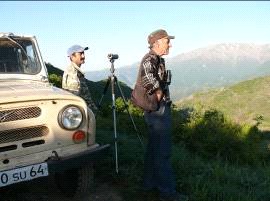

We have conducted mapping of nests, and survey of reproductive success, as well as we have investigated their feeding, reproductive success and analyze collected data on GIS Arc View.

The project includes education of local inhabitants about importance of rodent-eating raptors for agriculture and nature ecosystems. During the project, those students, who have completed BITC courses in Acopian Center for the Environment, have been trained in the field data collection. Two of the students, Grigor Janoyan and Tsovinar Hovanisyan have completed their Bachelor and Master’s degrees on the topic.

Long-legged Buzzard Buteo rufinus, outskirts of Gusana village, Shirak region of Armenia.

Map of study area of the Long-legged Buzzard Buteo rufinus in Armenia

Results:

Our study shows that the density of Long-legged Buzzard varies in different parts of Armenia. For example, the mean distance between the nests (nearest neighbor distance) is 1.98±0,19km (n=10) in Vedi district, while in Vayots Dzor region the mean distance is 3.04±0.3km (n=5); t=3.14, p=0.008. The difference in density seems correlated with steepness of surrounding area, since the Vedi district is generally more flat, than the Vayots Dzor region, which indicates that probably Long-legged Buzzards prefer habitats with less steepness of slopes. Most probably it depends on hunting technique of Long-legged Buzzard, which catches the prey on the ground dropping down from 5-10m. The other limiting factor is cliff availability, since in Armenia Long-legged Buzzards breed only on cliffs. Although LLB does not show dependence on the height of the cliffs and can place the nest on the height from 2 to 30m, it does not breed on trees, like in some parts of its area in Siberia.

The concluding results of the study were presented as a poster on the International Raptor Conference in autumn 2009 in Switzerland. We continue monitoring and conservation of Long-legged Buzzards in Armenia.

In the frames of the study a GIS shape file was developed, covering all cliffs and rocky massifs of the entire territory of Armenia.

Relevant publication:

Some habitat preferences of Long-legged Buzzard (Buteo rufinus) in Armenia

Hovanisyan, T., Janoyan, G., Schaefer, M., Aghababyan, K.

// 7th Conference of the European Ornithologists’ Union 2009. Zurich, Switzerland, 21-26 Aug 2009.

Levant Sparrowhawk Pilot Survey 2009 In Armenia

ACE (American University of Armenia, Yerevan, Armenia)

ACCL (Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, Pennsylvania, USA)

Red fields – study areas

Acopian Center for the Environment (AUA) in cooperation with Acopian Center for the Conservation Learning (Hawk Mountain Sanctuary) in 2009 there was conducted a pilot nest survey of Levant Sparrowhawk – one of the least known Western Palearctic raptors.

Several long term trips were organized to Aragats Mt and Meghri area, Yerevan city parks were surveyed as well on a frequent basis.

Field trips took substantial part of the project during April – August.

The main aims of the survey were:

- to standardize the methods of Levant Sparrowhawk nest searching

- to obtain an idea of breeding density, to identify habitat preferences and nesting success

The surveys have successfully resulted in overall 17 breeding sites/pairs.

Click on photo above to enlarge.

During the surveys a nest searching technique was developed and tested as most suitable from few other methods tried.

For all of the surveyed sites and nests there were recorded various parameters, such as nesting site GIS data, habitat description, behavior of breeding birds, nestlings and fledglings, interaction with other species and various other ecological information. Data on food was collected and taken few video footages and a number of photographs.

The information collected in 2009 helped to achieve initial objectives of the pilot project and will significantly contribute to the future surveys of the Levant Sparrowhawk in Armenia.

Distribution, abundance and habitat preferences of the lesser spotted eagles of Armenia

Acopian Center for the Environment 2007-2009

The Lesser Spotted Eagle (Aquila pomarina) inhabits almost all deciduous forest regions of Armenia. Due to economic and energy crisis and following economic growth in Armenia from 1990-s until now the land use pattern and the forest management in Armenia was strongly altered. The mentioned factors might have a negative impact on the large forest raptor species since they are more vulnerable and sensitive to changes in their habitat. Considering that the following objectives were chosen for particular study:

- to refine knowledge on distribution and abundance of Lesser Spotted Eagle in Armenia

- to study habitat preferences of the species

- to identify current and potential threats for the species

Foraging Lesser Spotted Eagle

Results

Based on the data collected during 1998-2007 it was possible to conclude the following:

- Distances between neighboring nests are 14. 2 and 14. 3 km (based on 4 nests)

- The average distance between the nest and limits of the hunting territory of a pair is 4.05 ±0.39 km

- The maximum possible population size of the species in the country, is preliminary estimated as about 48-52 pairs

The species in Armenia is facing to a number of direct and indirect threats, such as lack of enforced regulation in use of pesticides, poaching, human disturbance during breeding season and habitat loss.

Habitat of the Lesser Spotted Eagle (left) and its nest on the oak tree (right)

Outcomes

- The article regarding the subject was published. K. Aghababyan, V. Ananian, S. Tumanyan. 2008. To the Distribution and Abundance of Lesser Spotted Eagles in Armenia. // Research and Conservation of the Greater and Lesser Spotted Eagles in Northern Eurasia. Materials 5th Conference on Raptors of Northern Eurasia Ivanovo, February 4-7, 2008

- Several amateur ornithologists were trained in data collection and analysis and one of them, Tatevik Tamazyan, a student of Biological Department of Yerevan State University defended a Master’s Thesis on the subject “The Ecology of Lesser Spotted Eagles in Armenia”

- The results of the project were used for the new edition of the Red Data Book of Armenia and would be useful for the future forest management planning and environmental assessment procedures.

Hawk Mountain Acopian Learning Center Raptor Conservation Training

To date 4 trainees from Armenia have participated in this program. They include Karen Aghababyan, Vasil Ananian, Grigor Janoyan and Siranush Tumanyan.

Please visit the website: http://www.hawkmountain.org/

International Raptor Count

Autumn Migration – Batumi, Georgia 2008-2009

- Acopian Center for the Environment (Armenia)

- Youth in Action Programme (Belgium)

- PSOVI (Georgia)

Raptors are essential part of the wildlife, indicating the health of ecosystem. Change in the Raptors’ number might indicate different type of environmental issues. One of the easiest ways to get imagination of the abundance of different raptor species is to count them on migration since they are getting together on special areas, called “bottleneck sites”.

One of such sites is situated close to Batumi in Western Georgia (Ajaria), on the Black Sea coast, which is close to another raptor counting place – Borchka in Eastern Turkey. Hundreds of thousands of raptors fly through the area during autumn migration (from late August to October).

One of such sites is situated close to Batumi in Western Georgia (Ajaria), on the Black Sea coast, which is close to another raptor counting place – Borchka in Eastern Turkey. Hundreds of thousands of raptors fly through the area during autumn migration (from late August to October).

In 2008 the activity involved 28 volunteers and student trainees from Belgium, Holland, Georgia and Armenia. In 2009 other countries have joined the initiative, such as Turkey, France, Sweden, Holland, Belgium, Georgia etc. Apart from participation in the count ACE also took part in organizing and implementing the “Young Birdwatchers Exchange Program”, which aims to bring together birdwatchers from a number of countries. In frames of this project ACE has distributed a recruitment announcement in Armenia, interviewed applicants and selected the most appropriate candidates. Before leaving to Batumi the selected applicants were provided with preliminary training in Armenia, both in auditorium and in the field. ACE provides each of the local candidates with a copy of “A Field Guide to Birds of Armenia”, a pair of binoculars and a spotting scope for use throughout the count.

Upon arrival to Batumi, Karen Aghababyan as a leader teacher gives an intensive raptor identification course for the first three days for all the students of “Young Birdwatchers Exchange Program”.

Upon arrival to Batumi, Karen Aghababyan as a leader teacher gives an intensive raptor identification course for the first three days for all the students of “Young Birdwatchers Exchange Program”.

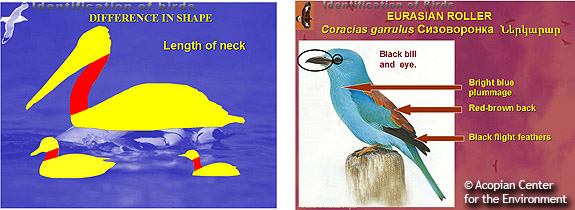

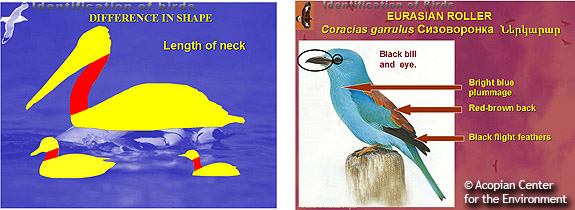

To teach the student ACE is using a raptor Section of the Bird Identification Training Course (BITC).

Some Results

During the counting period (by 6-22 /Sep/2008), there were counted 815374 raptors in average more than 67000 per day. We had huge number of Honey Buzzard, Black Kite, Montagu’s Harrier, Booted Eagle, Levant Sparrowhawk, etc., and also Snake Eagle, Osprey, Lesser Spotted and Steppe Eagle, etc.

During the count of 2009 the Crested Honey Buzzard (Pernis ptilorhynchus) was recorded, the second time for Caucasus.

During the count of 2009 the Crested Honey Buzzard (Pernis ptilorhynchus) was recorded, the second time for Caucasus.

More detailed info you can find at www.batumiraptorcount.org

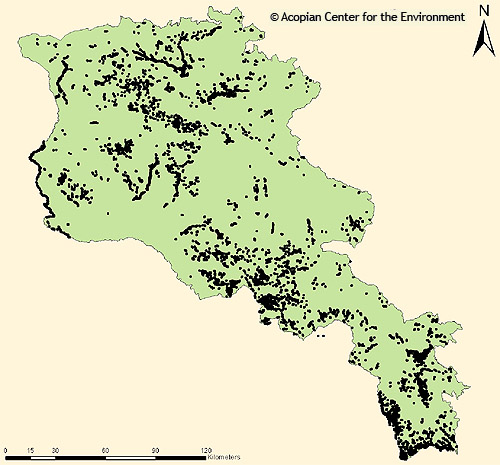

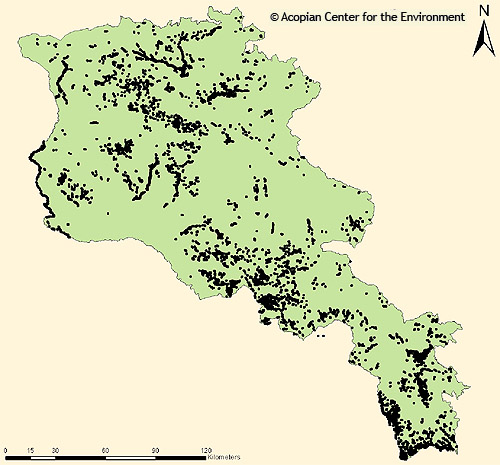

European Breeding Bird Atlas Monitoring

This project will fill gaps in the National Strategy of Biodiversity Monitoring regarding the inventory and information management on breeding birds of Armenia. It will also provide input to the European Breeding Bird Atlas, where Armenia is underrepresented. The European Bird Census Council recently appointed Dr. Karen Aghababyan as the National Coordinator of the European Breeding Bird Atlas 2. The project will trace the 3 long-term changes in breeding bird species’ distribution and abundance, as well as their habitat degradation caused by climate change and human-induced threats.

Currently, Armenia is divided into 10km by 10km grids. The field data collection routes are set up. The counting methodology is piloted. Over the next four years, Dr. Aghababyan will organize large-scale fieldwork involving hundreds of professionals and volunteers. The European Bird Census Council will use the country-specific atlases to compile a European-wide atlas, the EBBA2. With the massive amount of bird data collected, the EBBA2 will become one of the most comprehensive biodiversity data sets in the world.

Birds in my Backyard

The Acopian Center for the Environment sponsors a conservation-education competition called ‘Birds in my Backyard’ that encourages school children to build birdfeeders, observe the birds, and take a photo or draw a picture of a bird that comes to the feeder.

Support this program designed especially for Armenian children.

Students can win prizes and participate in the ‘Sun Child Environmental Festival’, another event that the Acopian Center for the Environment actively supports. This festival puts special emphasis on the youth and children’s participation in discussing current environmental challenges in the region. Besides competitive film screenings and photo exhibitions, hands-on activities such as field trips, tree planting and trash collection take place regularly.

“The competition is more than a competition; its aim is education. It offers children the opportunity to look at nature from a different angle. I hope that these children will become students of the American University of Armenia when they grow up and will continue to protect nature.” —- Dr. Jennifer Lyman, Ph D.

Past winners of the ‘Birds in my Backyard’ competition.

Bird Identification Training Course

The Acopian Center’s ‘Bird Identification Training Course’ (BITC) was initiated in 2004 with a group of 15 students. Since then, over 450 people have participated in this course. Classes are in three languages (Armenian, English, Russian) and conducted for local as well as foreign students. Anyone interested is welcome to attend. You do not have to be a student at AUA to attend. The classes are held in a friendly and enthusiastic atmosphere. We have had students of all ages – from 12 to 68 years old!

Course participants learn how to identify the different bird species in Armenia and how to observe them in nature. The course is aimed at people of all skill levels. We have a Beginner course and an Advanced course. Each consists of 30 lessons in which the students learn to identify at least 100 to 200 different bird species that occur in Armenia. The Beginner course has three field trips (to Lake Sevan, Lori region, and Aragats Mountain) and the Advanced course also has three field trips (to Armash fish-farming ponds, Noravank gorge and Dilijan forest) where birds studied in the classroom will be seen in their natural habitat. We provide binoculars and other optical equipment for observation during the field trips.

Classes are held once per week for 1 hour, from September 18 to May 30.

At the completion of the course, and after passing a test, each student will receive a certificate that they have completed the course. And the best students in the class will get a complimentary copy of the Armenian version of “A Field Guide to Birds of Armenia”.

Conserving the rich gene pool of wild relatives of wheat cultivars in Armenia is an urgent concern, as more and more land is disturbed by growing economic activity, land privatization, and other factors. Therefore, it is extremely important to evaluate the different Armenian populations of wheat and other cereals, and to conserve this valuable material. This can be achieved through periodic population monitoring, conservation in situ, and through collection of a seed material for preservation ex situ.

Conserving the rich gene pool of wild relatives of wheat cultivars in Armenia is an urgent concern, as more and more land is disturbed by growing economic activity, land privatization, and other factors. Therefore, it is extremely important to evaluate the different Armenian populations of wheat and other cereals, and to conserve this valuable material. This can be achieved through periodic population monitoring, conservation in situ, and through collection of a seed material for preservation ex situ.